Almost a month ago, I participated in the healthcare synthetic data hackathon organized by the Hospital Clínico de Madrid. The topic that struck me the most was that, despite the efforts and huge investments in information systems, quality information is scarce. This makes an eventual transformation of the healthcare system through data and artificial intelligence almost a pipe dream.

David Rey, Ph.D.

December 18, 2025

Although, in reality, I wasn't entirely surprised. In my experience over the last few years, this problem is recurrent in any sector. Even in digital-native companies, obtaining quality data requires a change in the way of working, and we already know that "culture eats strategy for breakfast"... and sometimes there is nothing more rigid than the human brain.

But soon, as the day progressed, I calmed down a bit. It seemed that if the real data didn't exist, we could build a sufficiently good replica (synthetic data). Although clearly, it is still "invented" data, and in an environment as sensitive as this, a second question came to mind: is it good enough?

Almost immediately, I remembered the construction process of DeepSeek R1 at the beginning of this year, where—simplifying to the extreme—the reasoning model was trained using data generated by an auxiliary model (DeepSeek R1-Zero). Through reinforcement learning, the model acquired increasingly sophisticated reasoning capabilities. A relevant part of that success lay precisely in the use of synthetic data.

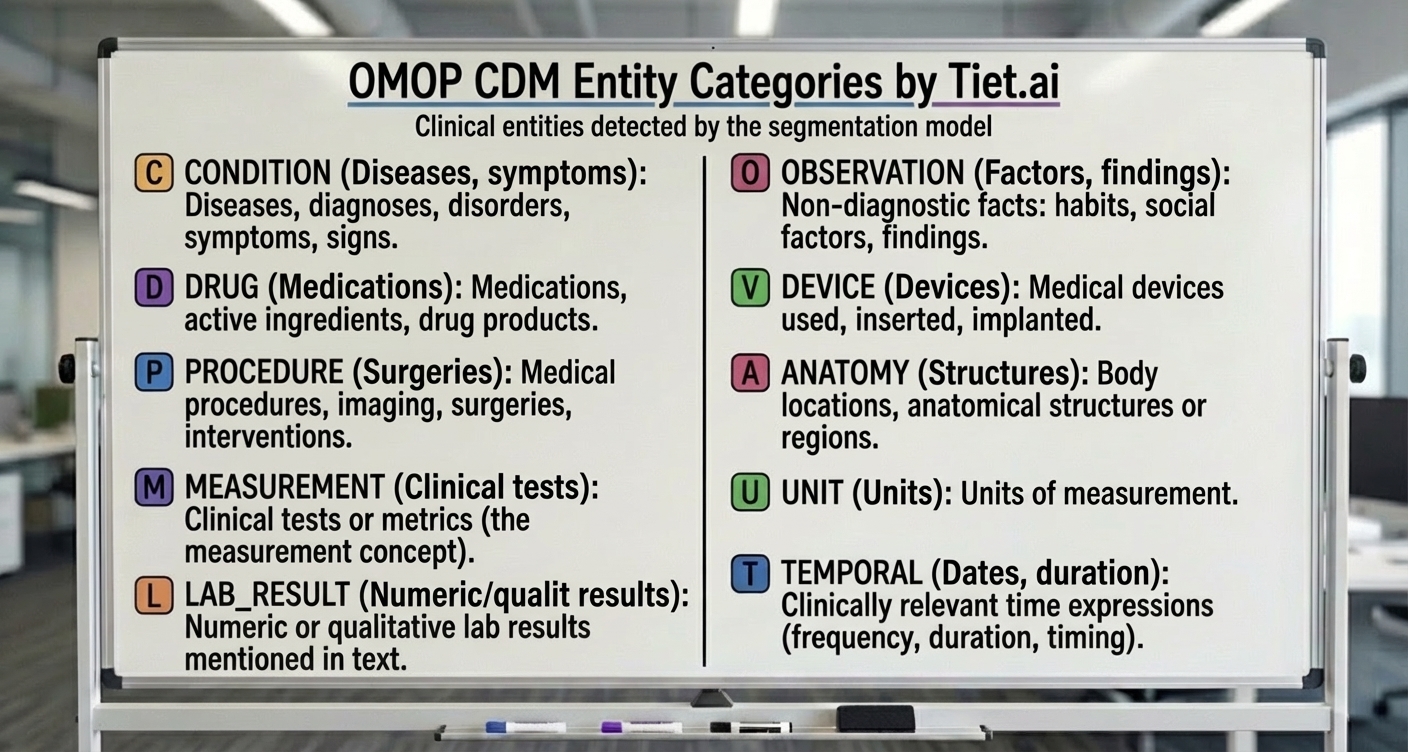

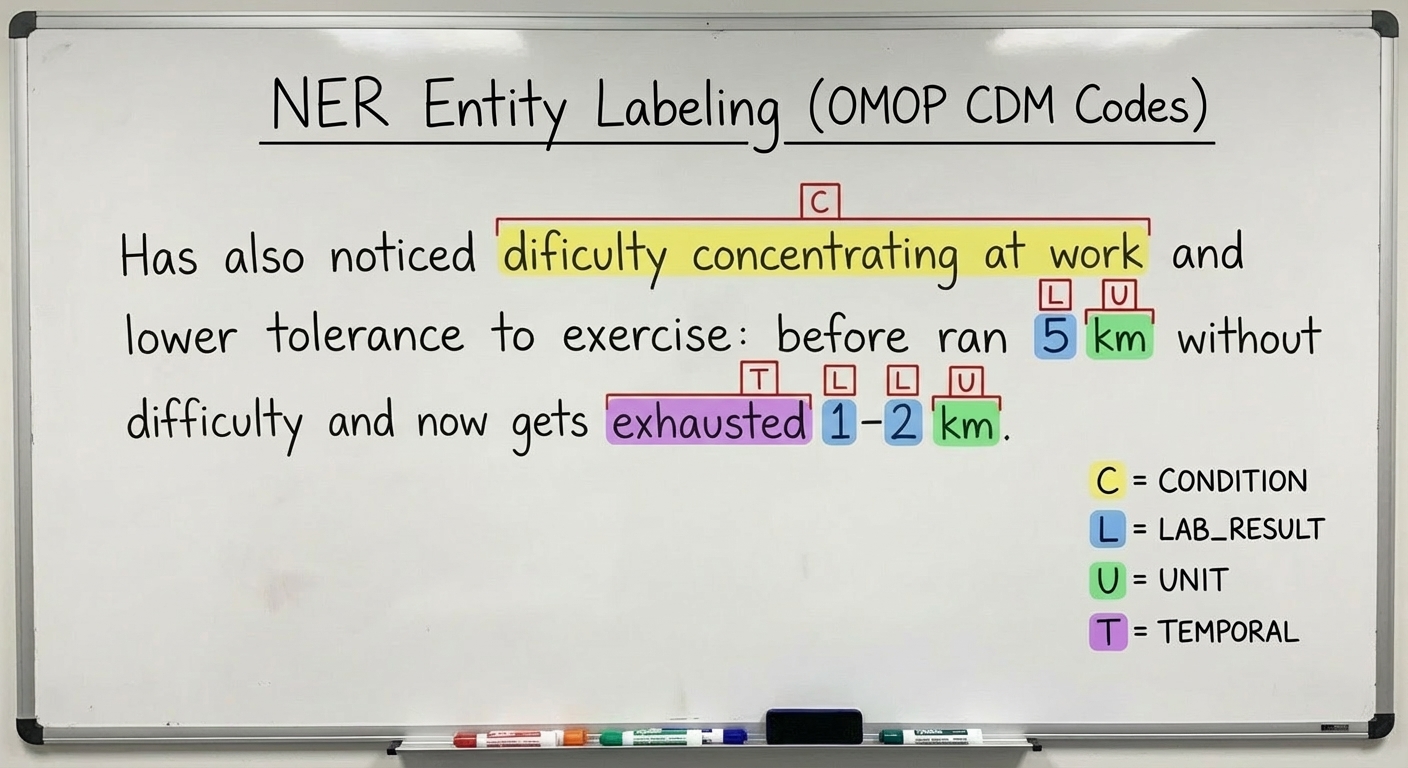

Figure: OMOP Common Data Model entity types

On the other hand, in recent weeks at Tiet.ai, we were improving the data entity identification module over free text, following the OMOP CDM data model (which aims to be a common and standardized data model that collects any type of clinical data).

Our goal was to manage to create a very efficient and precise system that treated large volumes of texts from the health system, disregarding their structure a priori: clinical histories in natural text, discharge reports, follow-ups, etc.

The problem is not new, because these types of issues suffered from scarce levels of precision with traditional natural language processing techniques. However, the recent appearance of Large Language Models (LLMs) and their reduced versions (SLMs) have opened a window for improvement: technical complexity has fallen, yet the cost and times required to execute large processes remain high.

Would it be possible to improve the approximations of more traditional text entity tagging (which are more efficient) through the use of synthetic data? That is, can we build a model capable of detecting elements in the text with the following types?

In particular, I had focused on specific models based on BERT-type architectures, like Clinical Bert, but oriented to my task. The first problem I had was that I needed to build a database, and the second was how to ensure that I hadn't actually committed overfitting due to the inbreeding of consuming the data that I myself had produced.

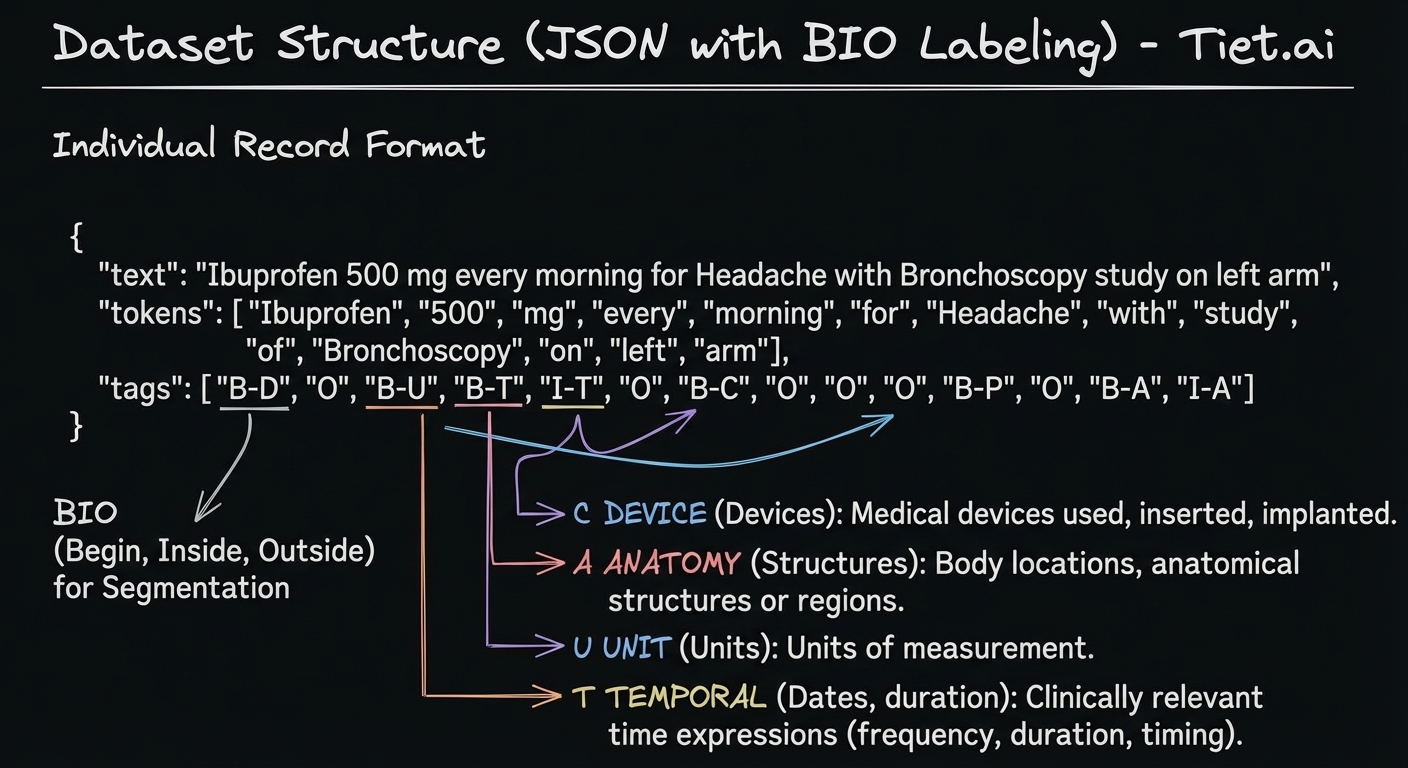

So I got down to work to build the dataset with this format:

Image: Dataset Structure (JSON with BIO Tagging)

In total, 20,873 records would be generated, distributed into three groups:

- Train set: 16,699 (80%)

- Test set: 2,087 (15%)

- Validation set: 2,087 (15%)

These data have not been generated completely at random; rather, it is forced that the records contain a minimum proportion of positive cases for each category, as well as negative or strongly negative cases.

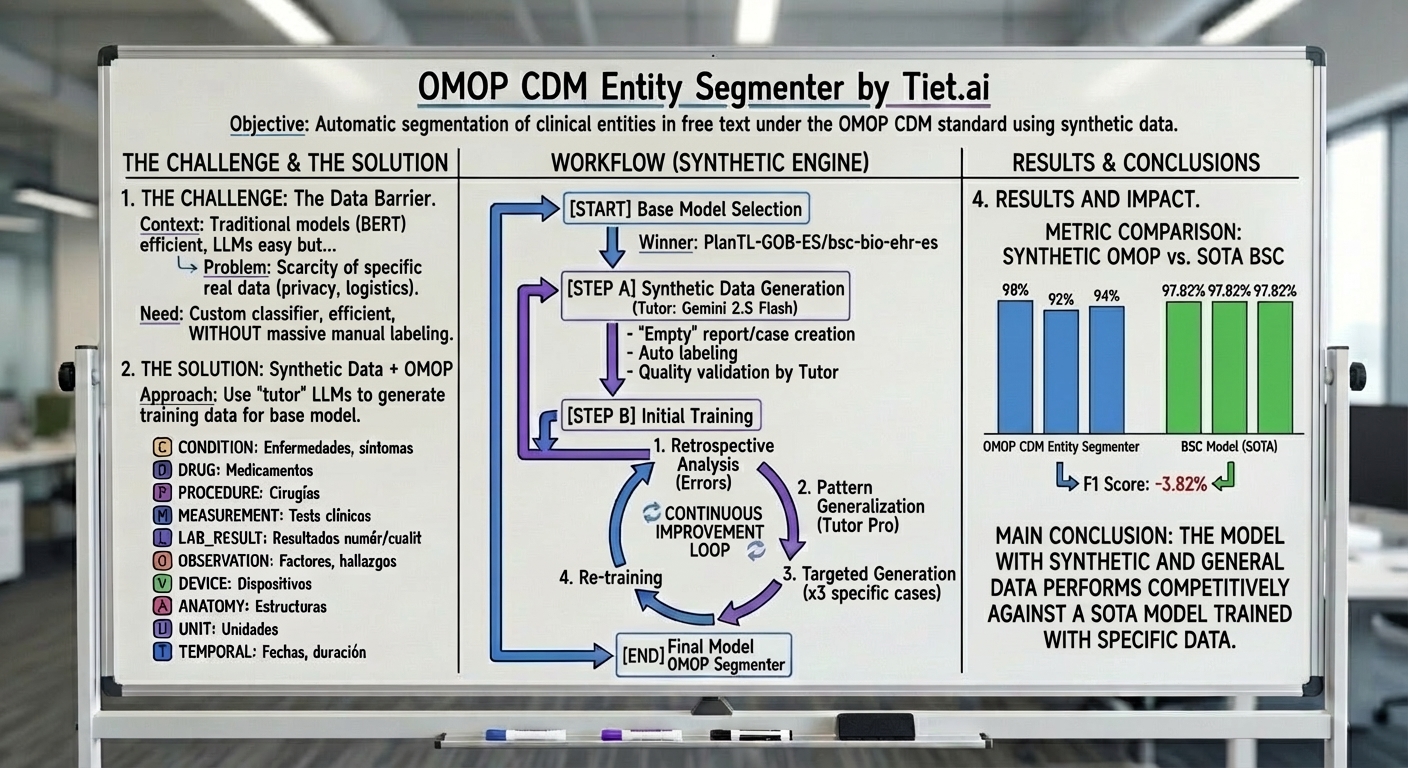

How do we build the dataset and the model?

The general idea is to build a dataset, refined by generalizing the observed errors. The process consists of a series of steps:

- Generate synthetic data using a large tutor model.

- Validate the quality of the synthetic data using another tutor model, to ensure the quality of the data used.

- Divide the generated dataset into 3 disjoint parts: (1) Training (60%), (2) Test/Validation in training (20%), (3) Out-of-sample Validation (20%).

- Perform fine-tuning of an efficient and small model, which incorporates domain knowledge but does not include the validation set. In this case, it would be PlanTL-GOB-ES/bsc-bio-ehr-es pre-trained on 278K documents and clinical notes.

- On the original validation set, we analyze with another tutor model (Gemini 2.5 Flash) to generalize patterns of the data observed in the errors of the test set.

- For each of the errors, we will generate a new set of data with 3 observations for each pattern.

- Finally, we refine the model again in step 4 for 3 iterations, until the improvements in the system validation metrics do not improve.

Image: General Process / Workflow Diagram

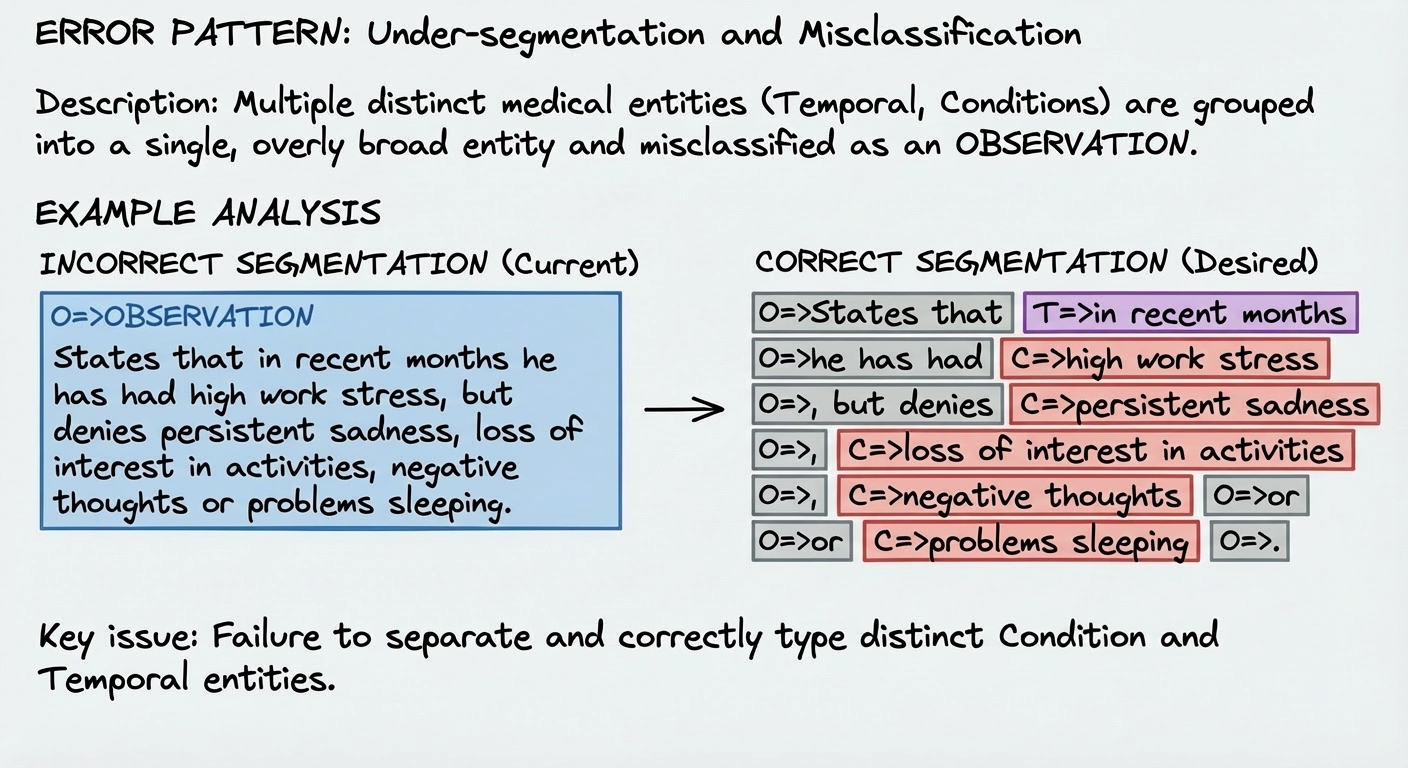

Image: Error Pattern Analysis

The image above better explains the key to this process: the tutor model reviews the errors and tries to give an explanation for an incorrect classification. This will be the input so that another model synthetically generates positive observations that reinforce a correct classification.

Are these results generalizable?

Now then, we already have a model that is capable of tagging clinical information precisely (with respect to our initial set), but the question is: is this quality real or is it only because we have "cooked" the data to our liking?

Before revealing any mystery, I pause to show the result of the model. As we can see, it is capable of identifying patterns in the text that correspond to the entities:

Image: Free text of a clinical note labeled by our model

The classification model had also obtained metrics that were much more than dignified:

- Accuracy: 98%

- Recall: 92%

- F1: 94%

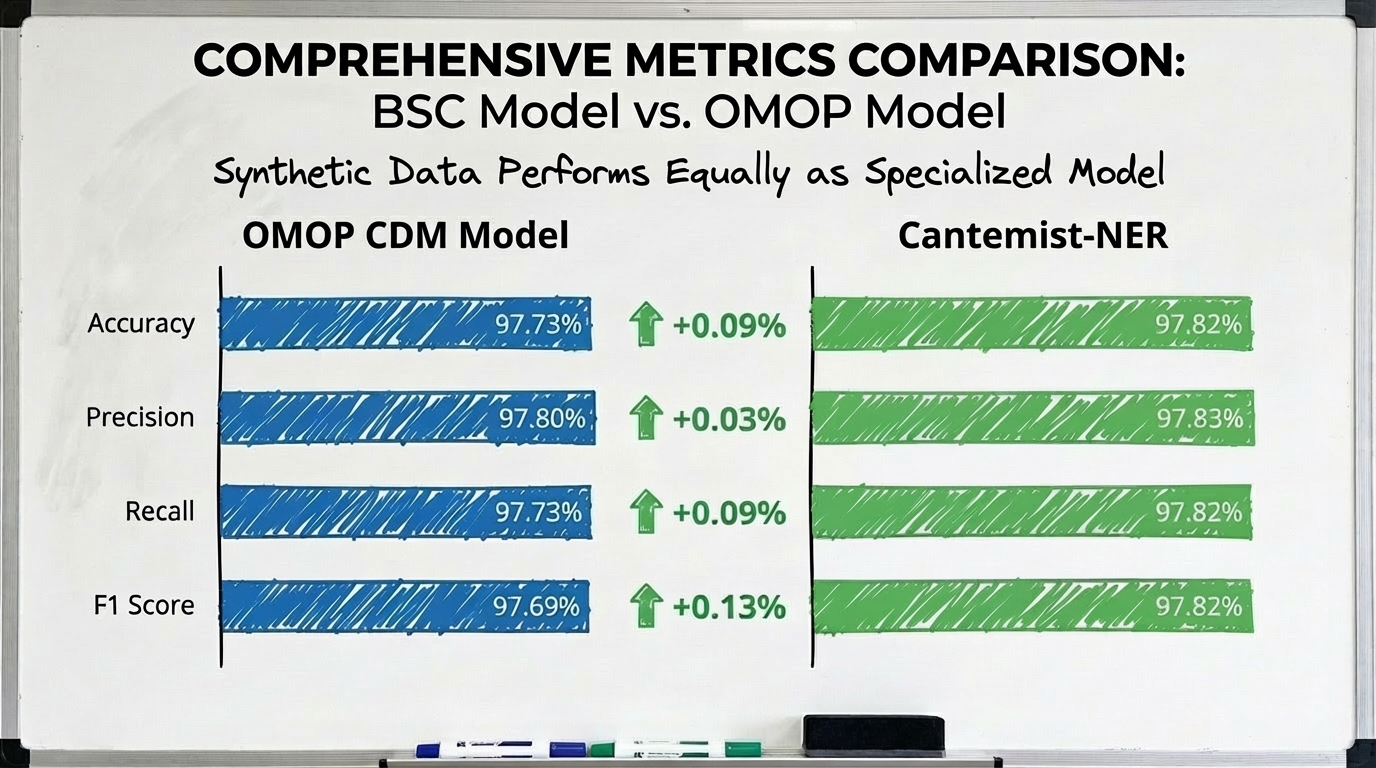

So far so good, but it was necessary to confirm that this experiment had generalized well. So, to do that, I decided to see how it functioned on a public disease dataset called CANTEMIST. By using this data, I ensured that I was evaluating results with out-of-sample data.

On the other hand, I wanted to compare the performance of my model with a similar one trained for a specific task. Luckily, SEDIA and the BSC had trained a classification model on the same base as mine but using CANTEMIST as the training and validation set. In their case, they had trained it with 30,565 observations.

To compare both models, I used accuracy measures at the record level (instead of doing it at the token level, as is done in the article of the model mentioned in the previous paragraph). The results were more than surprising; both models functioned in a very similar way.

Image: Model metrics comparison (BSC vs TietAI OMOP CM tagger)

With this, I was left a little calmer. The model constructed not only had precision levels similar to those achieved with a model trained specifically for the task, but it was also capable of classifying other types of entities as well. Thus, my hypothesis about whether synthetic data was useful in this domain had been experimentally confirmed.

Conclusions

To close, we could say that the use of systematically generated and validated synthetic data is not only technically viable, but it is a suitable alternative for cases where data is complex to obtain.

In sectors as sensitive as health, synthetic data can be a good alternative (sometimes it can even be the only one).

Key takeaways to keep in mind:

- It is possible to build multi-purpose models that offer performance comparable to highly specialized solutions, reducing dependence on ad hoc developments and facilitating re-use in different use cases.

- Knowledge transfer from large models to smaller, more efficient models allows balancing quality and cost, enabling productive deployments with lower infrastructure requirements.

- The pipeline based on generation, automatic validation, and iterative refinement of synthetic data minimizes overfitting risks and improves generalization.

- The very low cost of data acquisition ($35) represents a clear advantage of this method, especially in sectors where access to real data is limited or expensive.

- However, I want to make it clear that human labeling is ideal, but with this test, we can ensure that it is a valid source as long as we have validation sets available (as in our case).

![[background image]](https://webflow-prod-assets.s3.amazonaws.com/image-generation-assets/7aec9f70-e14f-43e7-a4bf-4098f770209d.avif)

![[interface] image of blockchain security setup](https://webflow-prod-assets.s3.amazonaws.com/image-generation-assets/d2c14179-5aa8-462e-9856-7fed1e5a0e72.avif)